On 11 February 1942, the Kriegsmarine's ships left Brest at 21:15 and escaped detection for more than 12 hours, approaching the Straits of Dover without discovery. As the German ships passed through the straits and on into the North Sea, British armed forces intercepted them, and attacks were made by the Royal Air Force, the Fleet Air Arm and Coastal Artillery. The attacks and bombardment were unsuccessful, and by 13 February all the Kriegsmarine's ships had completed their transit. In support of the German naval operation, the Luftwaffe launched Operation Donnerkeil (Thunderbolt) to provide air superiority for the passage of the ships.

German plan

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had arrived at Brest on 22 March 1941 after operations against Allied shipping in the Atlantic Ocean. Prinz Eugen appeared at dawn on 1 June at Brest Harbour after participating in Operation Rheinübung (Exercise Rhine). Here the ships were able to repair and refuel but were also subject to frequent air attacks. In light of this, Adolf Hitler ordered the Kriegsmarine to move the ships to their home bases. The Berlin Admiralty preferred the Denmark Strait passage but also considered the shorter but more dangerous route through the English Channel.

The matter was quickly resolved by Hitler in favour of the Channel, and all planning for the fleet transfer was passed on to the German Naval Command West in Paris. Although the operation would be under Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax, who commanded the Brest Group (flying his flag on Scharnhorst), Naval Command West under Admiral Alfred Saalwächter was responsible for all planning and operational directions.

As the operation had been ordered personally by Hitler, mine sweepers were deployed, additional radar jamming stations were set up, U-boats were sent for meteorological observations and several destroyers steamed westward down the Channel to Brest to strengthen the escort screen. Fighter ace Adolf Galland attended planning sessions on Scharnhorst and promised day and night fighter cover along the route.

Admiral Ciliax, who was personally pessimistic about the success of Operation Cerberus, had his own problems. His great ships were no longer the fine fighting machines they had been, nor did they look like it. While at Brest, many technicians and experts were detailed away for urgent requirements elsewhere. But morale on the ships was good; there had been no sabotage at Brest and the crews went ashore freely. Among the sullen locals there was no doubt that the ships were preparing to depart. To make the French believe (and pass on to the British) that they were heading for the South Atlantic, rumours were spread in town, tropical helmets were brought on board and French dock workers loaded oil barrels marked “For Use in the Tropics.”

British response

The British commanding officer was Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay of the Royal Navy. Available for him were six destroyers, which should have been on four-hour standby in the Thames Estuary but were not. There were also three Hunt-class destroyer escorts, but they had no torpedo tubes and so posed little threat to the well-armoured German ships, while the 32 Motor Torpedo Boats of the Dover and Ramsgate flotillas under Ramsay's command were counterbalanced by the German flotilla of E-boats. For various reasons, aircraft from the Fleet Air Arm, RAF Coastal Command and RAF Bomber Command were unable to provide an effective level of support.

This was partly because all services expected the Germans to time their dash through the Channel so that the most dangerous point at Dover-Calais (where the ships would need to move within range of British coastal batteries) would be passed by night. However the Germans considered it far more important to maintain the element of surprise for as long as possible by slipping out of Brest unnoticed at night, thus avoiding the 12-hour warning that an early daytime departure would have given the British. The British were wrong-footed by the audacious German move. Night reconnaissance patrols of the Fleet Air Arm did not detect the departure of the ships from Brest because their radars failed. The first indication that something was happening came from RAF radar operators under Squadron Leader Bill Igoe, who noticed an unusually high level of German air-activity over the Channel. The ships were then spotted in the Channel by the pilots of two Spitfires of RAF Fighter Command, but as they were under strict orders not to break radio silence and had not been briefed to look for the German fleet, they did not inform their superiors until they landed.

Fighter Command was not expected to be the first to spot the German fleet in the Channel, and valuable time was lost reporting the sighting up the chain of command and on to the Royal Navy and Bomber Command. Uncoordinated attacks by motor boats and six Fleet Air Arm Fairey Swordfish torpedo biplanes launched from Manston (in an operation formally referred to as "Operation Fuller")[2] failed to inflict any damage. However, the courage of the Swordfish crews was noted by friend and foe. Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde — a veteran of the chase of the battleship Bismarck — was lost along with his entire detachment of torpedo bombers, and was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously. Only five crew survived out of eighteen. Ramsay later wrote: "In my opinion the gallant sortie of these six Swordfish aircraft constitutes one of the finest exhibitions of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty the war had ever witnessed", while Ciliax remarked on: "...the mothball attack of a handful of ancient planes, piloted by men whose bravery surpasses any other action by either side that day".

RAF Bomber Command's response was tardy; only 39 of the 242 bombers which took part found and attacked the ships and no hits were scored. In addition to the bombers, 398 Spitfires and Hurricanes of Fighter Command flew several sorties on 12 February 1942. Altogether, 675 RAF aircraft (398 fighters, 242 bombers and 35 Coastal Command Hudsons and Beauforts) took off to search for and attack the German ships.

At noon on 12 February, the Channel guns of the Coastal Artillery went into action. The South Foreland battery with their newly installed K-type radar set started to track the ships of the Brest Group coming up the Channel towards Cap Gris Nez. At 12:19, the first salvo was fired; since maximum visibility was five miles, there was no observation of fall of shot by either sight or radar. The "blips" of the K-set clearly showed the zig-zagging of the ships and full battery salvo firing began without verifying fall-of-shot. 33 rounds were fired at the German ships, which were moving out of range at 30 kn (35 mph; 56 km/h), but all missed.

The six destroyers assigned to Ramsay were taken by surprise. Instead of being on station, they were practising gunnery in the North Sea. They steamed south to intercept the German fleet, but arrived in time to fire only one salvo of torpedoes, all of which missed. Counter fire from Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen severely damaged the destroyer HMS Worcester, which suffered 24 dead[3] and 45 wounded. Several salvoes from Gneisenau destroyed the starboard side of the bridge, and the No.1 and No.2 boiler rooms. Prinz Eugen hit the destroyer a further four times, setting it on fire. Captain Fein, aboard Gneisenau, ordered firing to cease, believing the destroyer to be sinking.

Outcome,

By mid-morning on 13 February, Admiral Ciliax sent a signal to Admiral Saalwächter in Paris: "It is my duty to inform you that Operation Cerberus has been successfully completed."

The British services (RN, RAF and Army) had failed to stop the ships of the Brest Group before they reached the safety of German home waters and had suffered severe damage to a destroyer and lost 42 aircraft. The Germans had suffered unexpectedly small damage and losses: Scharnhorst hit two mines, off Flushing and Ameland, but arrived safely at 10:00 on 13 February at Wilhelmshaven (the damage took three months to repair). Gneisenau hit one mine off Terschelling, but suffered little damage; the magnetic mine exploded some metres off the ship, making a small hole on the starboard side and temporarily knocking one of her turbines out of action. The ship was brought back to action after thirty minutes and she continued with the "lucky ship", the undamaged Prinz Eugen, which had suffered one dead from attacking British aircraft. Both ships then tied up at Brunsbüttel North Locks at 09:30. The torpedo boats T13 and Jaguar were slightly damaged by bomb splinters and machine gun fire, the latter suffering one killed and two wounded; of the Luftwaffe air umbrella over the ships, 17 fighters were lost with eleven pilots.

In Britain, the mood was sombre. An editorial in The Times of London read: "Vice Admiral Ciliax has succeeded where the Duke of Medina Sidonia failed. Nothing more mortifying to the pride of our seapower has happened since the seventeenth century. [...] It spelled the end of the Royal Navy legend that in wartime no enemy battle fleet could pass through what we proudly call the English Channel."

However, after the war, author Stephen Roskill noted: "The German Naval Staff, however, summarised the outcome as a 'tactical victory, but a strategic defeat'". These three powerful warships were no longer a menace to the Atlantic convoys but were instead re-assigned to the defence of Norway against an imagined invasion. The St Nazaire Raid a few weeks later eliminated the threat to the North Atlantic convoys by capital ships of the Kriegsmarine. This elimination of the threat was made even more so when only ten days after the operation, on 23 February, Prinz Eugen was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS Trident, destroying her stern and being knocked out for nearly a year. Gneisenau's luck ended a few days later on 26–27 February at Kiel when she was heavily damaged during British air attacks and effectively put out of the war.

The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen

The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen

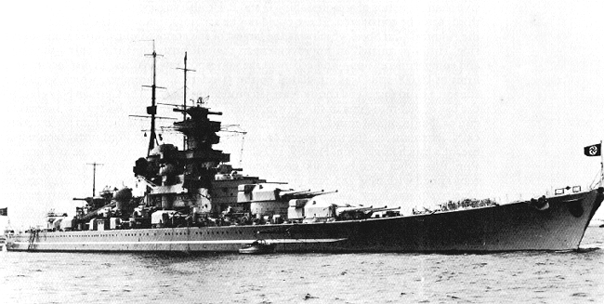

The battlecruiser Scharnhorst.

The battlecruiser Gneisenau

The battlecruiser Gneisenau The Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber.

The Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber. The Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fighter.

The Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fighter. Messerchmitt Bf-109G fighter.

Messerchmitt Bf-109G fighter. This is the map of the 3 German captial ships' escape through the Engish Channel.

This is the map of the 3 German captial ships' escape through the Engish Channel.

No comments:

Post a Comment